Main Page/BPHS 4090/Choloplast Translocation

Required Components

- Stock culture of Eremosphaera viridis

- Glass slides, cover slips and micropipette

- Nikon Optiphot Microscope

- Radiometric Probe (Model S471 Portable Optometer, UDT Instruments)

- Cool Snap CCD Camera and MicroManager software

- Blue and red band-pass filters

Objective

To observe the wavelength dependence of light on chloroplast translocation in the acidophile green algae Eremosphaera viridis as well as describing a mechanism behind this response.

Introduction

Electromagnetic radiation is the driving force for photosynthesis. Plants and other autotrophs convert the energy of light into chemical energy used for synthesizing carbohydrates and other organic compounds, which heterotrophic organisms use for energy and other nutritional requirements. Photosynthesis is a unique process performed by plants, algae, and some species of bacteria. It consists of a series of oxidation and reduction reactions; the basic chemical formula is shown below:

|

|

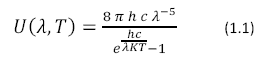

Photosynthesis would not be possible without the energy derived from light. Electromagnetic radiation enters the earth’s atmosphere from the sun where it is harvested by photosynthetic organisms. Wavelengths between 400 and 800 nm are used by photosynthetic organisms. The sun can be approximated as a near perfect blackbody with a surface temperature of 5800 K described by Planck’s Black Body Radiation Law, shown in Equation 1.1

|

|

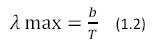

Where U (λ, T) has units of J m-2 s-1, h is Planck’s constant, K is Boltzmann’s Constant and c is the speed of light. The color temperature of the sun corresponds to a peak wavelength emission of about 500nm according to Wien’s Displacement Law (Equation 1.2)

|

|

Where b = 2.898 x 10-3 in units of m*K.

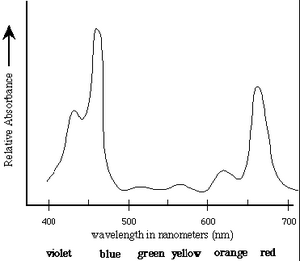

The first step in the conversion of the energy of photons to chemical energy is absorption by photosynthetic pigments, principally chlorophyll. The absorption spectrum of chlorophyll a is shown in Figure 1 [1].

|

Absorption Spectrum of Chlorophyll a: Chlorophyll a strongly absorbs

light at 465nm and 665nm. There is minimal

absorption of UV light as well as green/yellow light

which appears in the range of 500nm-600nm. These

absorbances are for chloroplasts isolated in a

solvent of a well-defined dielectric. In the cell,

additional pigments and heterogeneous dielectric

causes much broader peaks.

|

Chlorophyll is located inside the thylakoid vesicles in the inner membrane of the chloroplast. After absorbing a photon, an electron in chlorophyll transitions to an excited state. The excited state electron (exciton) is transferred to a photosynthetic reaction center to begin the flow of electrons through the electron transport chain, eventually to produce ATP (from a transmembrane H+ gradient) and reducing equivalents (NADP + 2e– + 2H+ —> NADPH + H+). Chlorophyll, now with one less electron, is chemically unstable and receives an electron from a water molecule (H2O). With the loss of 4 electrons from two molecules of water, molecular oxygen (O2) is produced, as well as 4H+ used for ATP synthesis. Oxygen, the waste product of photosynthesis, is vital for heterotrophs in the process of cellular respiration.

As light intensity increases, so do absorption events and the generation of excited state chlorophylls, and downstream electron transport. At a high enough light intensity, these can cause the formation of a variety of undesirable oxidative products that can damage the photosynthetic apparatus. Examples include triplet state chlorophyll, and various reactive oxygen species (through direct reduction of O2 to O2–, and subsequent formation of H2O2). The general term photo-oxidation is used to describe this damaging process. There are protective mechanisms to avoid oxidative damage [2]; one of these may be to decrease the absorptive cross-sectional area of chloroplasts by changing their location in the cell [3]. The phenomenon known as systrophe is described as the accumulation of cytoplasmic organelles around the nucleus [4, 5, and 6]. Systrophe of the chloroplasts is observed in the unicellular green algae Eremosphaera viridis when the cell is exposed to intensities of light greater than it would experience in its natural environment.

References

- ↑ http://www.bio.davidson.edu/courses/Bio111/Bio111LabMan/lab1fig3.gif

- ↑ Li, Z., Wakao, S., Fischer, B.B., Niyogi, K.K. 2009. Sensing and responding to excess light. Annual Review of Plant Biology 60: 239–260.